Dalit Music - The Sound of Dissent

Ritika Mishra

Published

Music is a part of the Dalit resistance against caste-based oppression, which hasn't died but has rather taken a dynamic and dangerous form in contemporary times. Why is there a need for Dalit music to be heard? The answer would be - to break the hegemony of upper castes and classes on art, poetry and music and to gain the audience it deserves in the mainstream market of cinema and music.

The word "Dalit" is often confused as a word related to the marginalised caste while etymologically it has its roots in the Sanskrit word "dal", which means "broken”, "crushed", or "oppressed". Over time, it came to be used in various Indian languages to refer to the people who were considered to be at the bottom of the social hierarchy in the caste system. Dalit music has been a form of resistance used by musicians, singers and artists since the time of Kabir, Tukaram, Namdeo, etc. Not only does the mainstream music ignore Dalit music and its contribution towards opposition to caste and class oppression in Indian society, but the academia also ignores it and therefore not many accounts of literature and the voice lyric poems are present.

The historical evolution of Dalit music starts from questioning the mainstream conception of God propagated by the upper class Brahmins and the consequent oppression they face in the society. Dalit music back then was based on the fundamentals of non dualism and the idea of presence of God within.

"I, a Mahar by birth, stand before you, Vithoba,

You are the Protector of Dharma, the breath of life itself.

I ask for no birth-based identity,

You guide me toward divine liberation,

You have created this world with equality."

— Excerpt from Chokhamela's Bhajan: "Maharacha bhet, purna vishwatma, Vithoba"

The Ambedkarite music questions the caste oppression politically, socially as well as economically, emphasising on social justice, caste resistance, Dalit pride and embracing Buddhism and empowerment through unity. The 'Bhima Koregaon' song refers to the Bhima Koregaon battle in 1818, where a small group of Mahar soldiers fought against the Brahmin-led Peshwa army.

"Bhima Koregaon ki ladai, Bhima Koregaon ki jeet!"

"Dalit raja, Dalit sena, Bhima Koregaon ki jeet!"

"The battle of Bhima Koregaon, the victory of Dalits!"

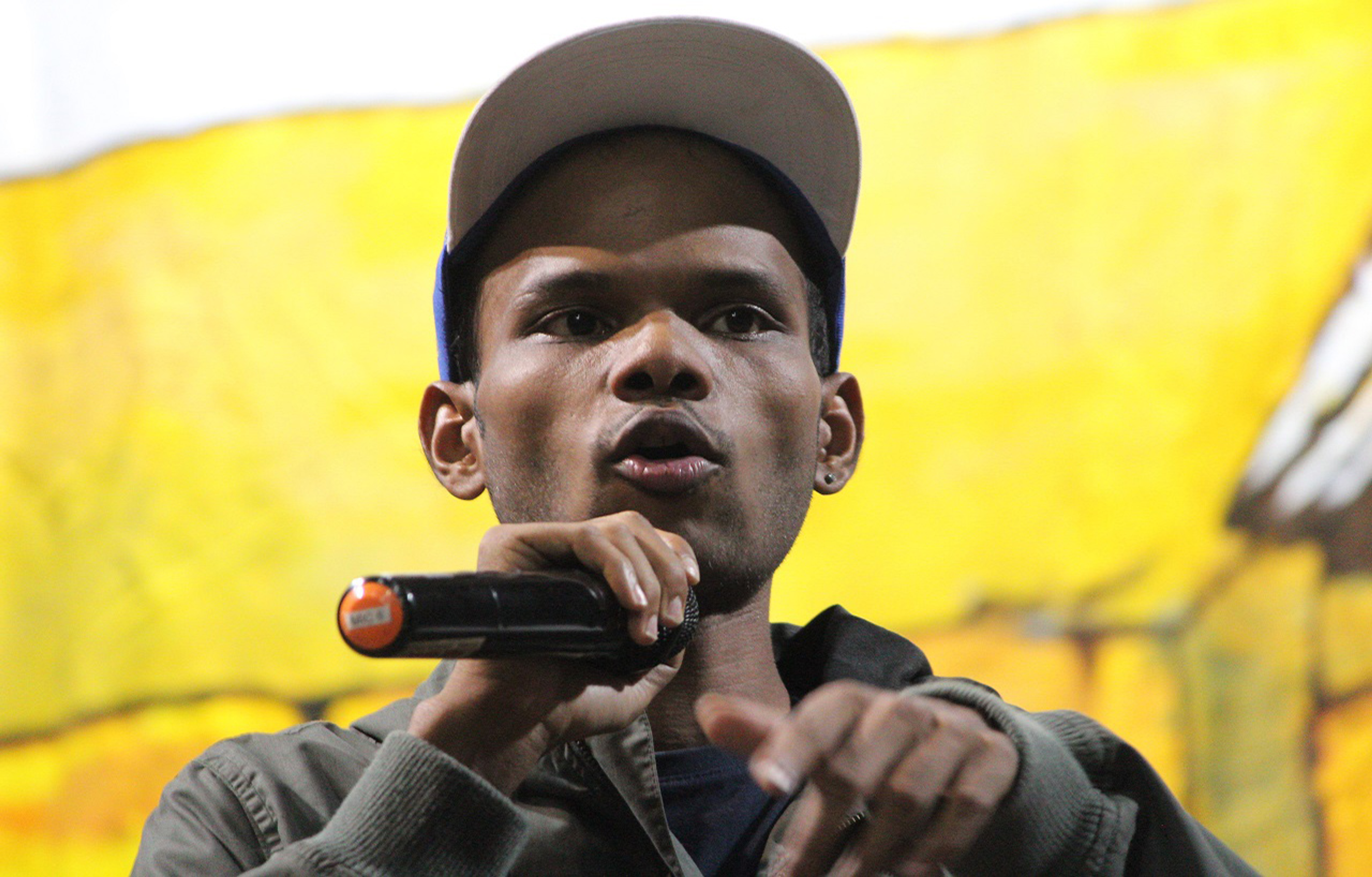

Although the audience is comparatively smaller, Dalit music still exists in the genre of Hip-Hop. Some of the contemporary conveners of Dalit Music are Gorati Venkanna, Ginni, Sumit Samos,The Casteless Collective, Sheetal Sathe, etc.

"Bhangi ka beta, aaj bhi jeeta hai,

Jitna bhi kathin ho, wo hamesha jeeta hai."

"The son of a Bhangi still survives today,

No matter how hard it is, he always survives."

– Excerpt from Bhangi Ka Beta by Sumit Samos [Currently PhD scholar at Oxford University]

Shilpa Mudbi, a vocalist and trainer from the Dalit community, has been vocal about the appropriation of Dalit music and culture in the arts. She emphasizes that the classification of Dalit-Bahujan art forms as 'folk' has often led to their decontextualization and erasure. In a December 2024 interview, Mudbi highlighted instances where songs unique to her community were used in mainstream productions without due credit or context. She pointed out that such appropriations not only strip the art of its cultural significance but also prevent the originating communities from benefiting equitably.

Mudbi co-founded the Urban Folk Project (UFP) in 2015 to revisit and reclaim songs and stories from her Dalit Bahujan ancestry. Through UFP, she collaborates with marginalized artists, including transgender women and devadasis, to preserve and promote their art forms authentically. She argues that genuine engagement with these art forms requires understanding the communities' lived experiences and histories of resistance.

In her TEDx talk, Mudbi raises critical questions about the ownership of folk music in the age of the market, challenging the commodification and misrepresentation of marginalized cultures. Mudbi advocates for co-working with Dalit artists, providing proper remuneration and credit, and maintaining long-term relationships to ensure that the cultural properties of marginalized communities are respected and preserved. She believes that addressing privilege and fostering equitable exchanges are essential steps toward preventing the erasure of these rich cultural traditions.

Dalit music struggles for recognition due to systemic caste discrimination, lack of institutional support, and cultural appropriation. It faces neglect from mainstream platforms dominated by upper-caste narratives, while stereotypes and economic barriers limit its reach. The music's themes of resistance challenge societal norms, often leading to suppression. Without proper representation, funding, or awareness, Dalit music remains marginalized despite its rich cultural and historical significance.

Dalit music and lyric poetry have come a long way, evolving into a blend of regional languages, culture, Dalit history, and pride within modern genres like hip-hop and rap. The recent movie Chamkila brought attention to this art form but didn’t gain the traction it deserved, reminding us how artists like Surjit Bindrakhiya and Amar Singh Chamkila have been politically targeted because of their caste. To break free from the homogenized culture of Indian music that often sidelines the political power of art, Dalit music needs broader economic investment and a larger, more diverse audience. Today, Dalit music is no longer just about narrating caste oppression—it’s about reclaiming history, pride, and dignity in every sphere: society, economy, politics, and, of course, music itself.

Ritika is pursuing Political science from Jamia Millia Islamia

Edited by- Nausheen Ali Nizami