Jamia’s New Leadership, New Controversy: Minority Quota in PhD Admissions Under Scrutiny

TJR Team

Published

In recent developments, Jamia Millia Islamia has emerged as a focal point of significant attention. In mid-February, the university released the results for its PhD admissions for the academic session 2024-25 across various departments, centres, and faculties. As a minority institution, Jamia Millia Islamia is constitutionally mandated to reserve 50% of its total seats for Muslim candidates. However, in the current PhD admissions cycle, the university has not only deviated from this reservation policy but has also allocated approximately only one-third of the total seats to Muslim students, thereby raising serious concerns about compliance with its minority status obligations.

The alleged violation of the reservation policy has sparked extensive discourse across the campus. However, despite the gravity of the issue, which pertains to a potential breach of constitutional mandates, there was a notable absence of widespread organised protest or collective outrage. During this period, approximately 15 students were suspended by the university administration for staging a sit-in protest within the campus premises without obtaining prior authorisation. Student organisations, which are typically active in mobilising resistance against such issues, appeared preoccupied with addressing the suspensions, thereby diverting their attention from mounting a robust opposition to the reservation policy violation.

In the interim, a candidate who participated in the PhD admissions process within the law faculty has filed a petition before the Delhi High Court, challenging the alleged infringement of the reservation policy. The matter remains sub judice, pending judicial adjudication.

How was the university able to declare PhD results without implementing the Muslim reservation?

The institution has become entangled in controversy following accusations that its newly appointed Vice Chancellor, Professor Mazhar Asif, is undermining the university’s minority character through systematic measures. The dispute arises primarily from revisions to the university’s PhD admission criteria, which detractors argue is biased in favour of non-minority applicants, thereby marginalising minority candidates.

Within a mere 17-day period following the appointment of the new Vice Chancellor, the Majlis-i-Talimi (Academic Council) and the Majlis-i-Multazimah (Executive Council) of the university enacted a revised ordinance that significantly altered the admission framework. The amendment transitioned from a mandatory selection process for minority candidates in reserved seats to a discretionary admission system based on the availability of eligible minority candidates to fill those seats. This modification has effectively institutionalised the practice of allocating reserved seats designated for minority students to non-minority candidates, justified on the grounds of an insufficient number of qualified minority applicants. This policy shift has raised critical concerns regarding the dilution of affirmative action principles and the safeguarding of institutional commitments to minority representation.

It is widely acknowledged that Muslim students face significant under-representation in higher education, particularly within central universities such as the University of Delhi (DU) and Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), where identity politics has become increasingly pronounced following their alleged ideological alignment with right-wing narratives. This systemic bias, particularly evident in the selection processes for PhD programs at these institutions, has compelled a substantial proportion of Muslim students to view Jamia Millia Islamia as a viable alternative for pursuing academic and research careers. However, the recent policy revisions at Jamia Millia Islamia, which alter the admission criteria for reserved seats, pose a significant threat to the educational rights of minority students. Students are of the view that this shift not only undermines the institution's commitment to minority empowerment but also represents a broader process of eroding the Muslim identity historically associated with Jamia Millia Islamia.

Background on Reservation Policy: The History of the University

During the colonial era, the decline of Muslim political and cultural influence in India was accompanied by a stark lack of access to modern scientific and Western education among the Muslim population. Recognising the transformative potential of education in empowering marginalised and backward communities, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan pioneered the establishment of an educational institution modelled after Cambridge and Oxford universities. This institution aimed to integrate the British education system while preserving Islamic values, thereby addressing the educational deprivation of the Muslim community.

Jamia Millia Islamia, a prestigious central university located in New Delhi, was founded in 1920 by a group of nationalist teachers and students, predominantly from the Western-educated Indian Muslim intelligentsia. This group had dissociated from Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) in response to Mahatma Gandhi’s call for the boycott of state-sponsored education during the Non-Cooperation Movement. Initially registered as a society under the Societies Registration Act of 1860, Jamia Millia Islamia later attained the status of a deemed university and was eventually recognised as a central university through an Act of Parliament in 1988. The National Commission for Minority Educational Institutions (NCMEI), in its judgement dated February 22, 2011, formally recognised Jamia Millia Islamia as a minority educational institution under Article 30(1) of the Constitution of India, read in conjunction with Section 2(g) of the National Commission for Minority Educational Institutions Act. Following this recognition, the university consistently adhered to a reservation policy, allocating 30% of total seats to Muslim candidates, 10% to Muslim women, and an additional 10% to candidates from Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs).

However, in the current academic year, the university has deviated from this established reservation policy, contravening the NCMEI’s 2011 judgement. This departure not only represents a failure to uphold institutional commitments but also constitutes a clear act of contempt toward the directives of the Hon’ble Commission.

Allegations of Violation

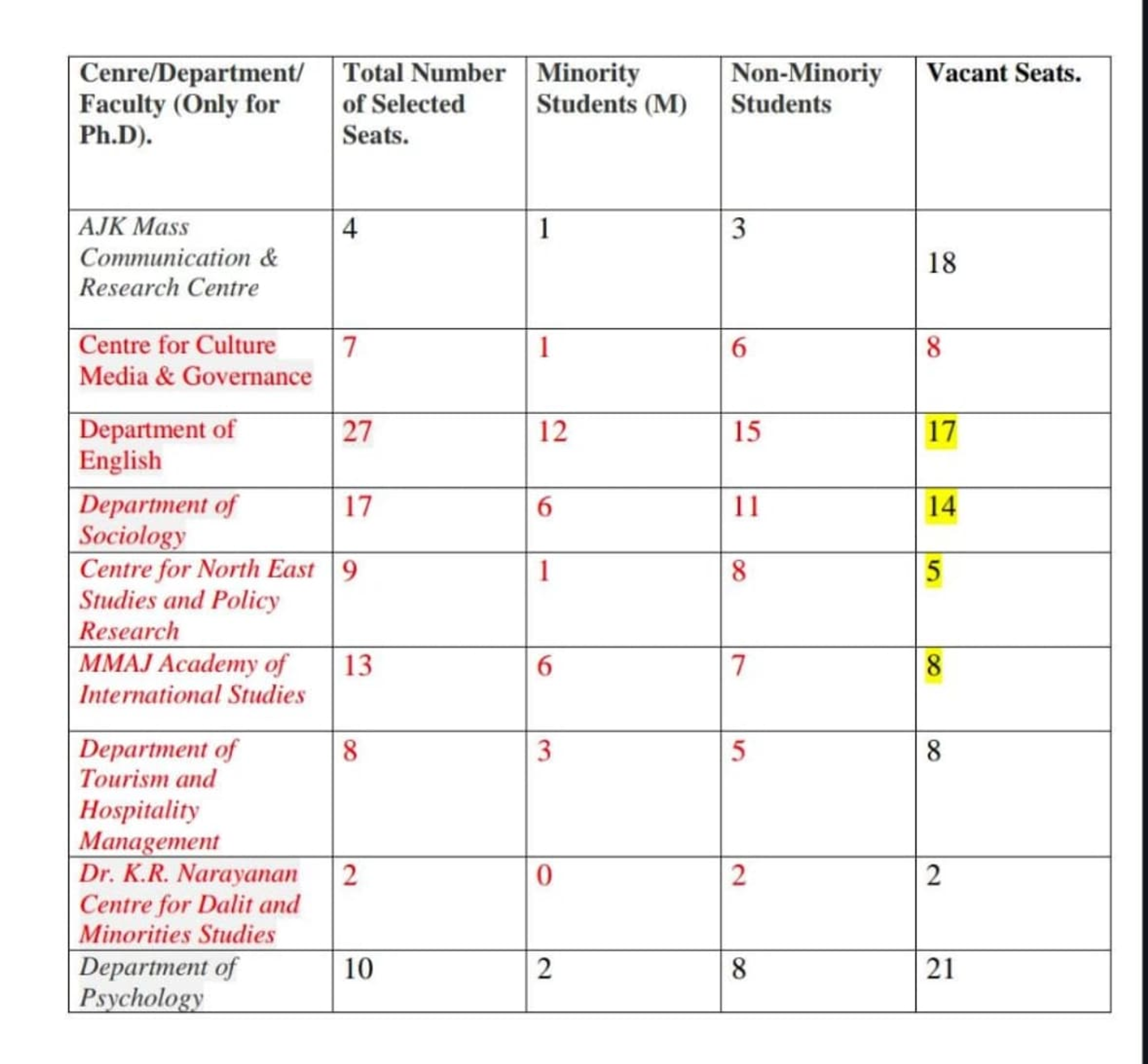

According to multiple complaints and the publicly accessible result PDF on the university’s admission portal, the AJK Mass Communication & Research Centre has allocated only one seat to a Muslim candidate, with 75% of the total seats being awarded to non-Muslim candidates. This pattern of disproportionate allocation is similarly evident in other departments. For instance, the Department of Psychology selected only two Muslim candidates out of ten, with the remaining eight seats being granted to non-minority students. Likewise, the Centre for Culture, Media, and Governance allotted one seat to a Muslim candidate and six seats to non-minority candidates. This trend of imbalance and alleged violation of the minority status quota extends to other departments, including the MMAJ Academy of International Studies, the Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research, and the Department of Sociology, among others.

When questioned about these discrepancies, the university administration categorically denied any violation of the reservation policy. Faculty members attributed the skewed allocation to an alleged lack of suitable candidates from the minority community to fill the reserved seats. This justification, however, has been met with scepticism, as it raises critical questions about the criteria used to determine eligibility and the broader implications for the university’s commitment to its minority character and constitutional obligations.

Impact of the Violation

According to the findings of the Sachar Committee Report, the Muslim community in India exhibits a higher degree of socio-economic backwardness compared to Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs). Despite constituting approximately 13-14% of the country’s total population, Muslims are significantly under-represented in higher education, with only 7.4% of Muslim individuals pursuing higher studies, in contrast to 35% of upper-caste Hindus. This disparity underscores the limited access to and participation of Muslim students in higher education, which serves as a critical mechanism for social and economic mobility.

The recent admission discrepancies at Jamia Millia Islamia raise critical questions about the potential soft saffronisation of minority institutions and the systematic curtailment of educational rights for Muslim students in India. This development appears to align with a broader agenda rooted in Hindutva politics, which seeks to marginalise minority communities by restricting their access to higher education. By limiting the opportunities for Muslim students to pursue advanced studies, this agenda challenges the emergence of a robust scholarly community among Indian Muslim youth, effectively weakening their potential for socio-economic and intellectual empowerment.

The under-representation of Muslims in these spaces weakens the community’s ability to contribute to and influence these critical domains. Consequently, the marginalisation of Muslim scholars in academia perpetuates a cycle of exclusion, limiting the community’s capacity to participate meaningfully in the nation’s intellectual and socio-political fabric. The current admission policies at Jamia Millia Islamia, if left unaddressed, could signify a deliberate effort to dismantle the foundational principles of minority education in India.

Fatima Zohra is a student pursuing MA Gender Studies from Jamia Millia Islamia.

Afan Abdullah is a student pursuing Law from Jamia Millia Islamia.

Edited By: Sidra Aman

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of The Jamia Review or its members.