Kotha number 64, on Delhi’s GB Road, which is mostly inhabited by Nepalese girls, is the most popular among the 100 or so brothels in this bustling market area. It is also considered the safest for customers, as the price of a single-sex is set at 300 rupees. For sex workers here, life is confined to the dark walls of the four-storeyed building filled with movie posters. Inside these walls, they cook, raise their children, and try to find love.

The intersection of tradition and reality is evident in the depiction of courtesans and sex workers in the Hindi film industry. The portrayal often evokes images of opulence, with courtesans surrounded by jewels, havelis, and nawabs. However, the truth remains that these women face significant stigma and hardship in real life. Regardless of the terminology used – whether it be sex worker, prostitute courtesan, or tawaif – the social stigma attached to their lives persists. Belonging to a highly denounced profession with no financial and familial support forthcoming, the latter years of the lives of impoverished female sex workers are spent in abject misery and poverty. The income earned is very meager with hardly any amount left to be saved. Most of the women live in one-room rented accommodations. Their access to medical facilities is found to be extremely restricted; specifically, there are no provisions provided to them during their menstrual time, childbirth, or even during the elimination of unwanted pregnancies.

This denunciation is never limited to these women or how shamefully they are paraded in the society but, rather, it penetrates their next generation as well. With limited access to adequate education, their children are cut off from other options in life. It is common for the children of sex workers to enter the sex trade when they reach the age of maturity. Girls become prostitutes and boys become brothel keepers or procurers. For the children of the owners of a kotha, they will probably take over the business of the kothas or engage in the trade by other means.

Breathing or not breathing, kothas are these sex workers’ ultimate home and graveyard. It is the place where they begin their life as a sex worker and end their lives as rejected bodies. Each kotha on GB Road has a specific number and is identified by it. There are others, which mainly offer women from the northeast who are of lighter skin color and can therefore fetch a higher price. It’s also an open secret that G.B. Road`s most notorious Kotha offers virgin girls.

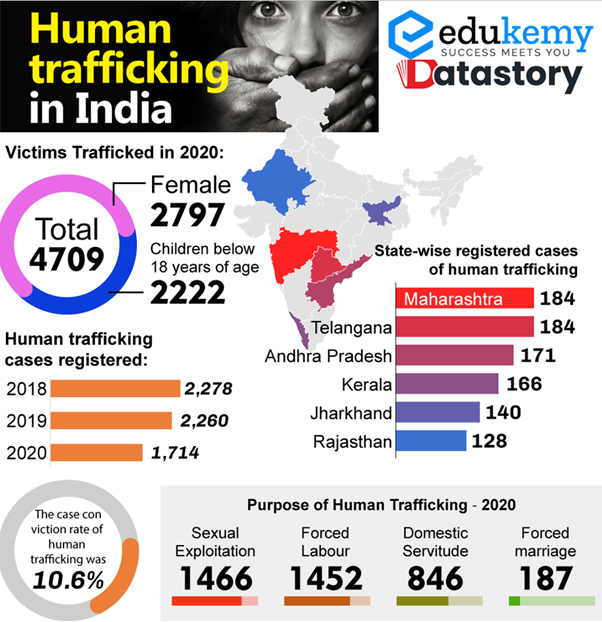

Numerous researches concerning prostitution and sex work produce data that enable us to understand the reasons behind their entering the sex trade – underlying poverty, poor living conditions, or a family of women trapped in this business. Although the majority of data undertake poverty to be a reason, there exists a whole universe of vulnerabilities behind such a choice. Also, it may be true that the bulk of women in this trade are trafficked (NCRB report, 2015) and therefore, forced into this profession against their will.

With beauty and attractive appearance at their side during their younger years, survival is somehow managed. But when due to factors like progressing age, accident, or physical assault, the quintessential good looks are compromised, it has a direct bearing on the income making the survival of the sex workers difficult. With no financial and familial help forthcoming, life becomes a daily struggle to make the two ends meet especially during the older years of the women of this highly marginalized and vulnerable group.

The sex trade knows no religious boundaries, despite the portrayal of sex workers in cinema being often restricted to specific religions. According to the 2011 census, the majority of sex workers identified as Hindus (66%), followed by Muslims (28%) and Christians (6%), representing a greater proportion than their share in the national population. However, religious affiliations become immaterial as trafficked women are forced to change their identities, appearances, and names to be fixed as sex workers. During an interview, Sunita, a widowed Muslim sex worker from Bengal, shared her poignant experience of having her original name Munnawara changed to Sunita by the madam at the brothel when she was trafficked to Delhi. She reflects on still following Islamic practices but adopting a Hindu identity to command respect in the community. Another sex worker, Kishori, emphasizes the societal perception that a woman’s respect is linked to her husband’s existence.

Historically, the British silenced the cultural tawaifs and shaped them into sex workers. Post-independence, society further deprived them of their dignity, compelling them to provide sexual gratification to men. The shift from being revered artists to sex workers reflects a societal failure. I am often reminded of Saadat Hassan Manto’s “Kali Salwaar” which compassionately delves into a sex worker’s longing for a normal love life, emphasizing the empathy needed when considering the lives of sex workers.

The shame is not theirs but ours.

Eishma Fatima is a student pursuing English Literature from Jamia Millia Islamia.

Edited By: Mukaram Shakeel

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings