The film is about youth and rebellion. It is about fathers and sons. There is a disagreement about the idea of India they all have; about India exploding in a thousand directions. In a sense the film is also about encapsulating all of life in an ideology, but life has a habit of slipping away from ideology. If Hazaaron still has resonance it is because it wasn’t caught up with the ideology.

Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi, a film about the waning romance with the revolutionary and violent Naxal Movement, released in 2005. The same year, the Salwa Judum, a state sponsored vigilante group out to massacre the Naxals, was unleashed along the ‘red corridor’- those states with Naxal presence. Just about a year after the release of the film, the then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh called ministers from these states to Delhi for a meeting where he called the Naxals: “the single biggest security challenge ever faced by our country.“

Of course a decade later the word Naxal would be liberally used to brand urban liberals. When Sudhir Mishra, the Director of Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi, made this film, one that is deeply sympathetic to the Naxal cause of villagers feeling alienated, of police brutality, and deep injustice; the word Naxal didn’t have any such connotations. But this doesn’t mean the film today feels dated. In fact, it is for that very reason the film still has such a huge following.

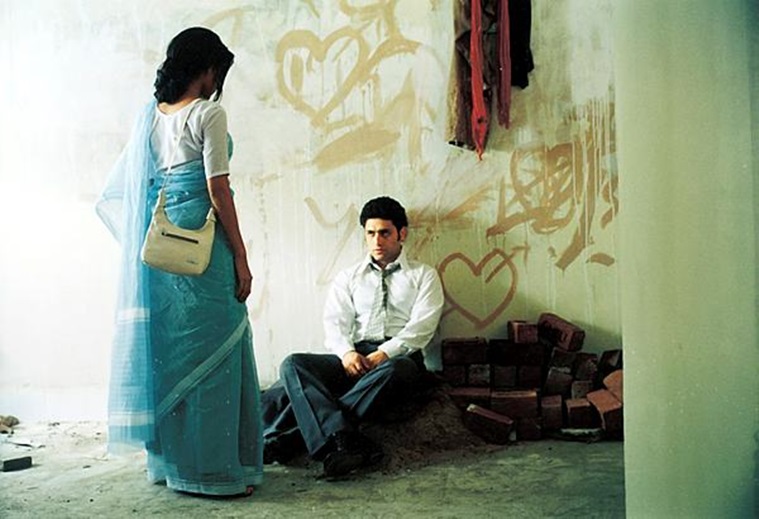

“Pandit Nehru made a horological mistake.” Thus begins Sudhir Mishra’s Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi, declaring (though not decrying) the so-called Nehruvian dream as a nightmare. “At the stroke of midnight when India awoke to ‘light and freedom’”, the world was not asleep. It was for instance, around two thirty in the afternoon in New York,” the film notes with irony. Released in 2005, the relatively low-budget, no-star Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi quotes from Nehru’s iconic ‘Tryst with Destiny’ speech on the eve of 1947, but the film is really about love and conflict in the time of Indira Gandhi. The daughter of India’s first Prime Minister and the infamous 1970s Emergency imposed by her in the most fascist fashion disrupting democratic ideals forms a heady backdrop for Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi.

With its depiction, and subsequent disillusionment with Nehruvian socialism, Mishra’s political drama recalls a time when revolution was in the air. In essence, Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi is JNU student politics come to life. The high-caste, privileged characters that populate Delhi of the film’s imagination are highfalutin forerunners of – to borrow from the vast and highly innovative vocabulary of the right-wingers – ‘Urban Naxals,’ ‘Twitter Libtards,’ ‘Tukde Tukde Gang’ and ‘Anti-Nationals.’ Characters in Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi talk about ideals, oppression, poverty, capitalism and inequality with passion but their bourgeois-by-birth background is not lost on the audience.

Mishra’s poetic touch and love for music is at par with his anger and bitter humour, all of which are beautifully embedded into the script. For instance, when Siddharth talks about establishing a new social order and says that life is not all about getting a “proper English education, fat salary and loving one’s parents”, it sounds funny because he’s speaking in English himself and he’s a beneficiary of the same convent education he’s pet-peeving about. The joke in the “loving one’s parents” bit isn’t exactly hidden either. Funnier still is a scene in which a rich landlord, down with a heart attack, agrees to be treated by a lower-caste doctor while his son objects. More hilarities: an heir apparent who still answers to the higher calling of socialism but cannot throw away the trappings of the good life.

The movie straddles all the big issues of the 1970s but never without a touch of poetry and dewy-eyed romance. It is Sudhir Mishra’s angriest and yet, his most optimistic film to date. Most importantly, Mishra deserves credit for seeking to expose the hypocrisy and double standards of the Left and its intellectual activism by revealing a huge gap between the naïve romanticism of the socialist theories and what it can truly achieve on the ground. The Leftists are totally disconnected, the film appears to argue, from the unpleasant realities as they pontificate in their ivory towers, far removed from where all the action is. This disconnect is best interpreted in a throwaway scene at a rally in which a farmer asks, “Who’s Hitler?” and a fellow seated next to him shakes his head, “He’s definitely not from our village.”

The film’s fundamental question, ‘Can socialism ever be a force for public good?’ draws a blank in the end. At best, crusader Siddharth is still trying to find an answer to it before his plunge into the Naxalite Movement. Shiney Ahuja’s Vikram was never fully on board while Geeta Rao, the film’s most mysterious figure, is the naif who is lured into it from time to time by her ex-lover. She submits eventually. Sudhir Mishra, however, has the final word. “I think it is about the vestiges of beauty that lasts when youth fades,” the Director told Hindustan Times in 2018. That’s why, he said, the title is an inspired moniker alluding to Ghalib’s philosophical abstractions. Nobody knows the answer, neither Marx did nor Ghalib. Certainly not Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi’s well-meaning radicals and their convenient idealism.

Varda Ahmad is a student pursuing Economics from Jamia Millia Islamia.

edited by: Rutba Iqbal

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of The Jamia Review or its members.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings