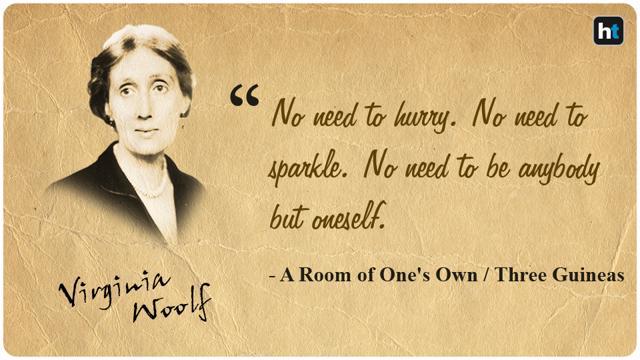

The twentieth century was an era of transition. Victorian ideas were put to question and the stability perceived by the nineteenth-century writers was nowhere to be found. British Empire collapsed, world wars ensued, and the way of life radically changed. New ideas emerged challenging the ideologies of the old institutions. Such developments manifested in art, including the English novel. The techniques utilized by the Victorian writers were criticized. Consequently, the writers of the modern world came up with new methods to articulate their expressions. Among the many influential names was a brilliant lady plagued by her own mind, known to many as Virginia Woolf.

“Examine for a moment an ordinary mind on an ordinary day.”

– Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Stephen, born in 1822 London, was, as she describes it, “born into a large connection, born not of rich parents, but of well-to-do parents, born into a very communicative, literate, letter writing, visiting, articulate, late-nineteenth-century world.” Her sophisticated background and her brother’s circle of intellectual friends after their parents’ death aided her inclination towards writing since her formative years. The circle of friends, famously known as the Bloomsbury Group, displayed an interconnected similarity of ideas that reflected in their works, including that of Virginia Woolf’s.

As a novelist and critic, Virginia Woolf lambasted the then-popular form of the novel. In her essay, Modern Fiction, Woolf elucidates upon her understanding of modern fiction. She writes: “The writer seems constrained, not by his own free will but by some powerful and unscrupulous tyrant who has him in thrall, to provide a plot… Is life like this? Must novels be like this?”

Virginia believed that the traditional form of the novel restricted the writers with its sequential mode of narrative-building. Instead, she rebelled by writing novels that were less rigid, less plotted, and more naturalistic in form. Her first novel, The Voyage Out (1915), though less audacious than her later works, experimented with narrative perspective. It revolves around Rachel, a young sheltered woman on a voyage to South America. As Rachel’s ship moves away, the passengers perceive their life in England differently than when they were in its midst. Distance gives them a new outlook; the destabilizing tendencies of modernism – its questioning of Europe as the essential center of world culture, its interest in how a certain angle of vision shapes subjectivity – begin to appear. In contrast to the plot-driven Victorian novels, Woolf’s debut novel did not have any mystery to solve or any revelations to make. The one serious romance is disrupted by a sudden death and the narrative is denied any structural closure.

Woolf’s characteristic method made its first complete appearance in her third novel, Jacob’s Room (1922). This novel marked a shift in the writer’s bibliography. It employed the modernist technique of stream of consciousness more boldly. The novel follows Jacob’s life, but he is seen mainly at a distance, through the eyes of other characters. The narrative itself is quite fragmentary so that the reader experiences the same problem faced by Jacob’s survivors—how to piece together his life. The momentary impressions, which shift and dissolve with the bewildering inconsequence of real mental processes, are revealed by the use of the internal monologue. This same method, handled with greater firmness, is again used in Mrs. Dalloway (1925).

Mrs. Dalloway, one of Virginia’s best works, is essentially without plot; what action there is takes place mainly in the characters’ consciousness. Woolf blurs the distinction between direct and indirect speech, freely alternating her mode of narration between omniscient description, free interior monologue, and soliloquy. Maureen Howard, an American novelist, writes that if ever there was a work conceived in response to the state of the novel, a consciously modern novel, it was Mrs. Dalloway.

To the Lighthouse (1927) shows a firmer mastery of stream of consciousness. The relationship of the Ramsay family achieves greater artistic unity than that found in her previous novels. She pays more attention to her characters’ mental processes. There is hardly any dialogue in the novel. It seems that the writer breaks from prose and becomes something closer to poetry. The most striking example is the title itself; the lighthouse is a poetic symbol that takes on different meanings for different characters. The use of poetic symbols suggests a more indirect, oblique, and tenuous approach to reality. For a writer such as Virginia Woolf, who has no definite vision of reality, the suggestiveness of these symbols is an essential part of her art.

Woolf truly mastered her art with The Waves (1932). The novel, perhaps her most experimental work, follows the consciousness of six characters with six internal monologues. She creates a six-sided lyrical impressionism to illustrate how each experiences events – including their friend’s death- differently. British author Amy Sackville remarks, “As a reader, as a writer, I constantly return, for the lyricism of it, the melancholy, the humanity.”

Her later works – Flush (1933), The Years (1937), and Between the Acts (1947) were mainly preoccupied with the transformation of life through art, the themes of flux of time and life, and a symbolic narrative. They were, however, not as brilliant as her previous creations. Among all her novels, Orlando: A Biography (1928) stands alone as the only fantasy. It describes the adventures of the eponymous poet who lives for centuries, meeting key figures in English literary history. Orlando is considered a feminist classic for exposing the artificiality of gender prescriptions.

Virginia’s works are presented through a carefully operated lens. Her narratives are without clear demarcations, moving from the inner to the outer to the characters fluidly. In her essays, Virginia condemned the novel of social manners, the kinds written by Bennett and Galsworthy. It wasn’t that she was not concerned with the realities of life. For her, the reality was inward and spiritual. Although the characters would follow their consciousness in search of the truth, Virginia did not end her novels with a solution. Her nonlinear forms invite reading not for neat solutions but an aesthetic resolution of “shivering fragments”. French director and screenwriter, Jean Guiguet remarked on the distinctive nature of Woolf’s reality:

“Her reality…is all that is not ourselves and yet is so closely mingled with ourselves that the two enigmas—reality and self—make only one…To exist, for Virginia Woolf, meant experiencing that dizziness on the ridge between two abysses of the unknown, the self and the non-self.”

Human consciousness is a chaotic welter of sensations and impressions. It is trivial, fleeting, evanescent. Woolf encapsulated it through the stream of consciousness. Although the technique was not new when Virginia came into the picture, it was through her works (along with James Joyce) that it became popular and vogue. Her lyrical style, with a keen sense of rhythmic and musical potentialities, is richly figurative and the images are precisely in keeping with the delicacy of her character analysis. The equilibrium between the lyrical and narrative art shows how the writer brilliantly achieves the telescoping of the poet’s lyrical self and the novelist’s omniscient point of view. It is a case of unified sensibility, that is, a blending of the objective and the subjective.

Among the many achievements of Virginia Woolf, perhaps the one she might be most proud of is her contribution to feminism. Long before the second wave of feminism, she had argued that women’s experience could be the basis for transformative social change. It is her success in contriving thoughts and ordinary actions, sound of the city, memory and the present, privacy and communion, bringing them all to life in the moment that distinguishes Virginia Woolf as a novelist. Her haunting language, her percipient insights into historical, feminist, and artistic issues, and her revisionist experiments with novelistic form during a remarkably productive career altered the course of Modernist and postmodernist letters.

Alisha Uvais is a student pursuing English Literature from Jamia Millia Islamia.

GIPHY App Key not set. Please check settings